|

Contextual Flexibility in Human Social Behavior

People flexibly adapt their behavior to different contexts, including interactions with different people. Rather than adopting a set of general rules that apply equally to every person across all situations (e.g., “give a dollar to everyone you meet”; “trust no one”), the mind instead brings to bear a complex set of cognitive processes that enable people to adapt their behavior across different contexts. By integrating approaches from psychology, cognitive neuroscience, behavioral economics, and other areas, we investigate how the mind constructs inferences about other minds and future scenarios and, in turn, how those processes and their outputs give rise to flexible human behavior. In addition to generating insights into human thought and behavior in the lab, we are working to test how well those insights can be used to predict patterns of behavior in the complexity of the real world. Some areas of current investigation are described below.

Uncertainty reduction in social decision-making

Humans frequently need to fill in gaps in information in order to make decisions. This is particularly the case in the social world, where much of the information needed to make a good decision cannot be perceived directly but must instead be inferred from an array of indirect cues. For example, although you might ideally want to know what another person thinks, intends, wants, or feels before deciding how to behave toward them, it is rarely the case that you have explicit information about these internal states of other people's minds. One area of our research examines how the human brain fills in the informational gaps that permeate our social world in order to guide decision-making. We use a combination of behavioral experiments, computational modeling, and and neuroimaging (fMRI) to investigate the cognitive processes through which people make social inferences given varying sources and degrees of uncertainty and how those processes and their outputs produce flexible social behavior.

Cognitive foundations of mental simulation

The ability to construct representations of events, ideas, or states that are not identical to anything we have ever experienced in the past -- that is, to engage in mental simulation -- is one of the most remarkable abilities of the human mind. Despite the importance of mental simulation for navigating complex social environments (e.g., considering how our actions will affect others, predicting what other people will do) and for making decisions about the future (e.g., predicting what we'll want for breakfast tomorrow; assessing how much we will want to travel when we're 70), the core mechanisms in the mind that give rise to mental simulation abilities are not fully understood. This aspect of our research tests hypotheses about the processes in the mind that support the ability to envision and value future outcomes and to make inferences and predictions about other people.

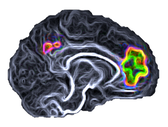

The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and the default-mode network (DMN) in human social cognition

One emphasis of our work is on understanding how features of the social context modulate the engagement of cognitive processes supporting theory of mind, or mentalizing, i.e., the act of inferring the mental states and personality traits of others. A particular focus of this research is on the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). One of the most consistent findings in cognitive neuroscience is that the MPFC tends to be more engaged when people think about themselves than when they think about other people. Yet this region is also consistently more engaged when thinking about people than when thinking about objects and is intriguingly engaged during a number of other activities, including episodic memory and decision-making. What process-level account of MPFC function can unify these findings? As part of the brain’s default mode network (DMN), the MPFC has been implicated in mental simulation -- the ability to transcend the current, first-person perspective in order to imagine future outcomes and the contents of other minds -- and it has been implicated in disruptions of social function, for example in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Yet despite its importance, and perhaps in part because of it ubiquity, a unified understanding of the cognitive processes it carries out has been elusive. We are investigating a set of hypotheses about the core functions of MPFC, its relationship to other DMN regions, and how best to understand its role in social cognition.

Is social cognition fundamentally "social"?

Given the particular challenges inherent in navigating complex social environments, does the mind have mechanisms specialized for social thought? Or does social thought simply rely disproportionately on domain-general mechanisms that happen to be particularly applicable to the way information tends to be structured in the social world? Over the last several decades, it has been shown that a particular set of brain regions responds more when people mentalize or engage theory of mind than when they engage in similar non-social tasks, that individuals can show deficits in social cognition while other abilities remain relatively spared, and that human social cognitive abilities might be qualitatively different from those of other animals. These observations have led some to suggest that the human mind contains cognitive processes specialized for social cognition. We are testing hypotheses about possible domain-general mechanisms that might serve as the building blocks of human social cognition.